There are many things to love about traveling to another country. Learning about different cultures is very exciting, because there is always something new to discover. Yet, what I like more is identifying the similarities – it is always fascinating to find out about what makes us the same across different cultures. I recently had the opportunity to discover these similarities and differences on a medical mission to China with Operation Smile.

Operation Smile is a non-profit organization that provides free cleft lip and palate surgeries to children all over the world, especially in hard to reach areas. Being born with a cleft lip and/or palate can result in many complications, including malnutrition from feeding difficulty, speech disorder, dental complications, and social isolation due to the stigma associated with a visual birth defect. In some cases, parents abandon these children because they do not have the resources to take care of them.

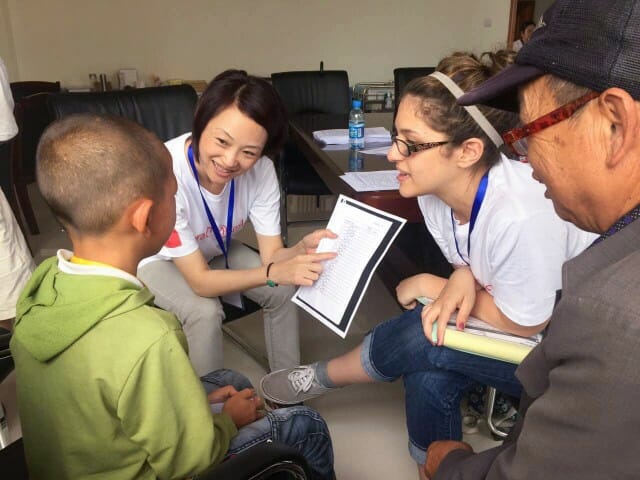

Missions are composed of surgeons, nurses, anesthesiologists, dentists, speech pathologists, child life specialists, and many volunteers and interpreters from the region. Missions begin with 1-2 days of screening patients followed by several surgery days. Unfortunately, not all children (or adults) who show up will receive surgery during that mission. Some cases take precedent over others. There are several factors that go into this decision, but babies and young children with a visual defect (cleft lip) are given first priority. It was disheartening to see a large number of adults with a remaining cleft palate, since they have suffered with poor speech for many years.

Screening day was definitely the most hectic for me as a speech pathologist. When working with cleft palate, the main speech concerns are resonance (nasality) and articulation (speech sound errors). Although the children spoke Mandarin or another Chinese dialect, not English, I could still reasonably assess these speech characteristics. But a speech pathologist assesses so many other facets: language development, voice, fluency, feeding, and even hearing to some degree.

By midday, it was announced that there were still 100 more patients waiting to been seen by the speech team. Simplifying my evaluation process was a challenge for me as I suspected I may be the only speech pathologist a child ever sees. I wanted each child to receive the same level of care as the next. The surgery days are when I felt I made the most impact. I visited families before or after surgery and was able to teach parents about their child’s speech and empower them to be speech therapists at home.

It is difficult to know where to begin when describing China. All the team members met in Kunming, the capital of the Yunnan province located in southwest China. From there, we took a five hour bus ride to our mission site in Wenshan City. This was a wonderful way to see the beautiful landscape of China, a noticeable contrast to the smog and pollution observed in Beijing. Wenshan City was not quite the rural area I expected. It was highly populated (around a million) although many Chinese volunteers from Beijing and Shanghai found it laughably tiny. I can’t imagine telling the volunteers how large my hometown was….they would have considered it a village!

Differences in China’s geopolitical landscape were also something that stood out to me. Although I knew China was highly censored, it did not register much with me until I could not access any social media accounts, YouTube, or Google. All websites took a rather long time to load. Video surveillance is heavy and I noticed it more throughout the progression of the trip. A large majority of China’s population is known as the Han Chinese, with ethnic minority groups referred to as ‘minorities.’ Minority groups seemed to encompass a significant portion of the families we treated this mission. China in itself is very diverse with differences in food, language, and landscape from province to province. The Yunnan province was one of the most ethnically diverse provinces in the country because it borders Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar, and Tibet. Our local volunteers were composed of Han Chinese and were as surprised by the living conditions of the minorities as we non-Chinese volunteers were. In general, the local people are reserved and keep to themselves.

I think what I found most surprising was how almost no one seemed to know what my profession was. Speech therapy and other therapeutic professions are entering China’s healthcare system at a painfully slow pace. Many of the people I talked to were not aware of any rehabilitative jobs. However, most families and volunteers acknowledged its value. Parents voiced a lot of similar concerns: “I cannot understand what my child says,” “s/he says a lot of words but it is unclear,” or “s/he does not want to speak because others do not understand them.” Several parents expressed gratitude that someone was concerned about their child’s speech and that there were even methods to improve it. One grandma asked, “Is there not a medicine that can cure his speech?” The translators (who were wonderful and without them my job would have been impossible!) frequently expressed how important they thought this education was as speech impacts so many areas of life. I was even interviewed by a Chinese volunteer because so little was known about the topic. Families from Wenshan were showing up at the hospital seeking out a speech therapist once they heard Operation Smile was in the city. Unfortunately, stigma associated with disability still seems to linger. One parent denied any problem at all with his daughter’s speech despite her unrepaired cleft palate. Some fathers simply stated, “that is the mother’s job.”

Overall, I found these families inspiring. Most parents in the world seem to be motivated by the same thing – they want the best for their child. Parents are concerned about the same things: “I’m worried about when s/he goes to school, how they will be treated,” or “I’m worried they will get frustrated when they are not understood.” In addition, these parents have had to overcome negative comments and warnings from friends and family. One family was told their child was that way because the mother used an axe to chop wood when she was pregnant. They were also told they were being cursed by God and punished for sinful behavior. One mother was told not to even attempt to raise her child because she would not be able to speak. From the USA to China,it’s important to empower parents to feel they can also treat their child’s speech. In remote areas where there are no speech therapists, it is the only thing that will help a child’s speech improve.

Children are universally inspiring, too – they have a persistent motivation to work hard and an unrelenting optimism that helps them conquer tough situations. An eleven year old girl with a cleft lip was not allowed to leave the house, even to go to school. She was restricted to cooking and cleaning at home although she expressed how badly she wanted to go to school and learn. Another child, a seven year old girl, was almost sold but then later abandoned when her parents discovered she had a cleft palate. Luckily, she was quickly adopted by a couple of rice farmers who had tried unsuccessfully to have children for years. Although the girl has a significant speech disorder pertaining to her cleft, she is not shy, has many friends, and loves to go to school to learn. She aspires to attend university one day.

To see such commitment and perseverance from parents and children was a beautiful experience. My profession allows me not only to help families, but to be inspired by them as well. This feeling of inspiration seems to be universal no matter where I am. I am truly grateful I was able to experience this firsthand in China.

Marissa Habeshy, M.S., CCC-SLP